The Ultimate Soviet Leader Rankings

No better way to celebrate the anniversary of the October Revolution (or, really, November Revolution if one disregards the then-utilized Julian Calendar), than with an ultimate ranking of the souls who got to shape Soviet Union from the upper echelons. We explore legacies, highlights & lowlights, as well as lesser known facts about the crema de la crema of the socialist powerhouse that seemingly dug communism’s grave for generations to come.

Rules & Clarifications

First things first: For obvious reasons, we are establishing a one-year in office cutoff point. Surprisingly, that doesn’t mean much other than disqualifying Georgi Malenkov, Stalin’s short-lived replacement who was forced out of office barely 6 months after taking over as part of a transition troika. With that in mind, the Soviet Union was headed by a total of 7 de facto leaders during a 70 year run, two of them for extremely short-lived and awful health campaigns. Compared to many European powerhouses which faced periods where they changed leaders like underwear, this was relatively impressive. Some might want to dismiss and take this for granted, given the generally held notion that these secretaries were immovable precisely because there was often no official way to get rid of an authoritarian leader other than through their death. Yet, there is a world where the constant emergence of factions, silent or loud disagreements within the party and folk could have given birth to multiple more removals and replacements.

To give this exercise a more meticulous and reliable outlook, we will present each leader with a score (out of 10) on four different domains; of course, the scores will be adjusted where need be to make sure certain despicable or admirable decisions receive the weight they deserve. So here we go:

i) social prosperity and advance in different facets of human welfare

ii) legacy and impact locally as well as internationally

iii) charisma, innovation and novelty initiatives, and the ability to implement those

iv) the human aspect, compassion, avoidance of violence- war-death where possible

Without further ado:

7. Joseph Stalin (1924-1953)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 6/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 3/10 |

| Charisma, Innovation and novelty | 8/10 |

| Human Rights | 0/10 |

| Total: | 17/40 |

He loved flowers and gardening. Pulled funny pranks on his colleagues. He invented photoshop. All due respect to Joe’s apologists, and particularly the vast number of Greek communists who are still somehow hesitant to denounce him, his last place finish ought not surprise anyone. Sporting the longest tenure in the much elusive office, Stalin led the USSR for 29 years (or 31, if you’re weird about positions), and naturally, him being directly responsible for millions of deaths makes numerical sense. That doesn’t justify the Great Purge, doesn’t justify using forced labor to further his industrialization, nor the annihilation of the intelligentsia just because their dissident status red flags were beeping. Where he receives high marks in terms of his inexplicable charisma (everyone thought he wasn’t the brightest, and yet nobody could do anything to stop his ascent) and societal advance via urbanization, he gracelessly loses in virtue of the inhumane means he employed to get there.

Highlights:

In preparing himself for stardom, Stalin was an expert at flying under the radar. One of the primary reasons he managed to jump to power was that nobody in the senior circles, Lenin and Trotsky included, ever really considered that he could go all the way up to General Secretary. They deemed him too plain, too little minded. He had a gift for taking sophisticated and ambitious Lenin ideas and simplifying them for the laymen, articulating them in manners that rendered them digestible to the common peasant. He developed into a master of internal politics, and it is no accident that he managed to remain in power for three decades, despite dragging the country through numerous abominable initiatives. He knew how to get close to and appeal to people that mattered in his contexts and get things done by them, and consequently be feared enough not to cause wild rebels against him. Last but not least, let us not forget unemployment officially did not exist in the USSR past 1930.

Nearly all of his highlights came with caveats. He led the WWII victory front, yet Germany already was in their final death throes after getting too greedy and stupid, advancing on more fronts than they could keep track of. He pioneered industrialization and led the metamorphosis of USSR from a mostly rural society to an industrial juggernaut via the Five Year plans; yet, forced collectivization gave no time to everyday workersto adjust, leading to genocides, famine and increased rather than minimized corruption.

Lowlights:

Seems like a lot of these were inadvertently mentioned in the highlights. Though one shouldn’t make the leap to label him a psychopath, Stalin was a ruthless autocrat who was prepared to go to unforgivable lengths for his ostensibly Marxist ideals. He was a Lenin believer till the bitter end, but unlike his predecessor and successors, he was ready to sell his soul to the devil to prove the socialist project could advance. Early along the way he lost track of pretty much every principle Marx hid in plain sight, bringing the ‘means justifying the ends‘ premise to its illogical extreme.

Another memorable stain relative to war strategizing was his rather pathetic foundering in anticipating Operation Barbarossa, although intelligence had repeatedly warned him. Even after realizing Hitler had trespassed the non-violence pact the two of them signed a few years back, he asked his troops to do what they could where border violations were made, but not to go as far as to cross the border and prevent an all-out invasion. He then followed up one mistake with another, refusing to accept his army’s eventual pleas to retreat and organize a counter, instead now asking them to go all out and die for the homeland. More than 300,000 troops either died or were captured those fateful days.

Slightly overlooked fun fact:

As aforementioned, perhaps Stalin’s less disputed accomplishment and positive legacy was throwing the last punch to the Nazis. What is not mentioned quite so often was his propensity to hide or go incognito after immense failures or individual disappointments. Right after his misfiring following the German invasion, he retired to his datcha and went AWOL. After about 10 days where he left his state headless, the state’s lead representatives paid him a visit to try and convince him to come back. Joe was in such a miserable condition that he actually thought they were there to arrest him, yet after some persuasion he decided to go back and be king again. There’s another world where Stalin had either committed suicide, or where his seniors did actually decide to detain and replace him (which he seemingly would have accepted), in which case his legacy and historical imprint look rather different..

Or is that so? Many other historians claim to have disproved this theory, instead arguing that the entire nervous breakdown story was later made up and perpetuated by Khruschev in his continuing attempts to defame Stalin. Joe knew exactly what was coming, and he just chose a safe place to hide and strategize in order to put forth a counterattack masterplan, along with testing his comrades’ loyalty to see if they had it in them to mount a revolt against his leadership. That perhaps fails to explain why he didn’t even announce the invasion to his people but had his foreign minister Molotov do it via radio, unless that also never happened.

Whether Stalin’s mental strength was steel-solid, or whether, among his other crimes and disadvantages, he actually left the ship without a captain and went AWOL at one of the most critical junctures for his project, remains up to us to decide.

6. Konstantin Chernenko (1984-1985)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 5/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 4/10 |

| Charisma,Innovation and novelty | 4/10 |

| Human Rights | 5/10 |

| Total: | 18/40 |

You are excused if you’ve never heard the dude’s name. Frankly, the fact that Stalin managed fewer points than him is the epitome of diminishing returns. Chernenko was effectively a temporary replacement following Brezhnev and Andropov’s deaths, an attempt to bide the party time before they could elect their next leader. So who better to represent this cause after two seriously ill heads who ended up dying before their time? Another old guy with questionable and failing health.

Highlights:

Despite knowing his stay at the top was brief and the same fate as his two predecessors awaited him, he had the decency not to strive too much and reach for the stars. Where many people in his place would try and carve out a legacy by invading a country, making Cold-war relevant remarks with deleterious consequences, or seeking to restore something a la nostalgic fetishization, he can be commended on the fact he mostly stood pat.

Also continued was the trajectory of nuclear arms control, and reaching a more or less solid agreement with the US about limiting nuclear forces throughout Europe. On the other hand, he did think some of the communist ideals were being lost irreversibly, so some of his few interventions included mini attempts to show people the virtues of the old principles.

Lowlights

He could easily have added a few legacy points by leaving Afghanistan alone, but much like Andropov and Brezhnev before him, he left matters unchanged, if not made them worse. The extent of the role that the Soviet Afghan War played in the eventual dissolution of the USSR is controversial, but as a leader who was also engulfed in it, our man cannot escape this lowlight.

He also did foster and encourage more censorship than Brezhnev and Andropov; the guy probably couldn’t help it, having been a pioneer in propaganda departments and matters for most of his career. Chernenko moreover decided to increase military spending, at a time when the country’s economy frankly couldn’t spare it, which led to the economy heading to shits briefly before he left his last breath.

Slightly overlooked fun fact:

Soviet leaders kept a tradition of opening a predecessor’s safe after the said person had died. Chernenko’s safe apparently was full of cash, and so were most of the shelves of his desks. Given that his cause of death was not dementia, but lung and heart ailment, it’s astounding that someone so distinctly aware of their perishing would not bother hiding or gifting the goodies.

Whether this was a joke played by people in his office, or he himself sought to fabricate some sort of who-dun-it mystery and add some intrigue to his postmortem can only be postulated. To this day there has been no revelation as to where this money came from. Maybe he wasn’t as boring a man as we all assumed.

5. Yuri Andropov (1982-1984)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 6/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 4/10 |

| Charisma,Innovation and novelty | 6/10 |

| Human Rights | 3/10 |

| Total: | 19/40 |

I have to admit I developed a slight affection for Andropov. Surprised he only ended up 5th, especially considering who a few of those above him were. What can I say? I have a thing for losers who weren’t in love with unnecessary violence and Yuri didn’t pass the test. The longest serving chairman of the KGB (15 long but also short years), unlike Chernenko, wasn’t soft. Make no mistake though; he wasn’t your typical KGB bore either. He was often referred to as the Soviet James Bond. He loved jazz, arts and movies; Fellini was reportedly his big crush. Though nowadays equally anonymous as his successor, he wasn’t quite determined to let his time pass by without making somewhat of a name for himself. If nothing else, Yuri was a determined reformer. A close reading of his impact could lead us to two immensely different conclusions, had he had the chance to govern as long as most other leaders did. There are indications that he could have grown to be worse than Stalin, and there are indications that he could have been the most efficient and somewhat acceptable leader the USSR (n)ever had.

Highlights

Andropov’s main beef was dissent. Naturally, you will say; what’s the point of a KGB head if he can’t cut a traitor’s throat or two? If that sounds counterintuitive to his ‘reformer’ reputation, it’s not. He was a reformer precisely because he saw the various sectors in society where corruption and/or laziness kept the Soviet dream from realizing itself. Among hunting and punishing dissent in poor-man Stalin’s style, however, he also hunted corrupt officials, policemen and other regional pseudoheads. He waged a bit of a war on unproductivity, sending police to cinemas and shops to see if work-excused people frequented the premises. It might seem very anti-uniony and a blunt violation of worker’s rights from today’s perspective, but it’s also well documented that foul play, fake sick leaves and random absences had gotten a little out of hand during the Brezhnev era. He furthermore enabled relative autonomy from state directive for certain industries which ended up being a boon for investment in much needed technology.

If nothing else, Andropov was the rare figure that occasionally learned from his past mistakes. After spending the first years of his KGB career overly intervening, he was the primary figure that obstructed the invasion of Poland in 1981, after the Poles started mounting their own little social revolution. The possibilities of what would have happened internationally in case of an invasion are endless, so Andropov gets some prevention points here.

Lowlights

Perhaps his most infamous nickname was “The Butcher of Budapest”. Before grabbing KGB lead duties, he happened to be the Ambassador to Hungary in 1956, and subsequently a leading mouth towards the suppression and crushing of the Hungarian Revolution. Although his future self was not particularly proud of the violence during then, he did posit this was the one time when brutal force was absolutely required if Hungary was to remain a soviet.

As we can understand, rather smartly, he undertook most of his abominable acts as a less high-profile figure when heading the KGB and before, rather than when he was Head Secretary. Andropov played a huge role in the Prague Spring of 1968, perhaps one of the premier events that diminished Soviet reputation in the Eastern Bloc and rapidly led to distrust that would eventually bring it down. What essentially happened was that Czechoslovakia, until that point one of the most loyal partners of the Eastern bloc, tried to implement a number of reforms that would permit a degree of decentralization along with other overrated human rights such as freedom of press. Andropov convinced Brezhnev (more on him later in the rankings) that this was all a CIA ploy and the Czechoslovaks were on their way to westernization, if not annexation. So Yuri sent tanks and drowned this baby before it could grow up. It’s an ironic twist of fate that the CIA gig was likely a conspiracy fathomed by Andropov, whereas support by Americans in the Polish solidarity movement (where, remember, he chose not to invade) was much more real.

Other zits in his resume include submitting perfectly sane dissidents to psychiatric hospitals, and, again, advocating for entry in the Soviet Afghan war, even though he was one of the adults in the room who initially opposed it.

Slightly overlooked fun fact

Dear Mr Andropov,

“My name is Samantha Smith. I am 10 years old. Congratulations on your new job. I have been worrying about Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war. Are you going to vote to have a war or not? If you aren’t please tell me how you are going to help to not have a war. This question you do not have to answer, but I would like it if you would. Why do you want to conquer the world or at least our country? God made the world for us to share and take care of. Not to fight over or have one group of people own it all. Please let’s do what he wants and have everybody be happy too.“

Whether this was an intelligent publicity stunt or not, Andropov took the time to reply to the above letter sent by a lovely 10 year old American girl who was obviously sick of nuclear attack drills at her primary school. He reassured her nobody wanted to press the red button, and even invited her to ‘Russia’. Samantha ended up accepting, and she and her parents made the trip some months later. She never got to meet Andropov, as by the time she showed up he was too ill to get out of the house, dying a few months later. Despite her youth, Smith managed to write a book about her experience and worked on some TV shows. Unfortunately, she didn’t carve a better fate than Andropov, as she and her dad died in a plane crash two years later…

4. Mikhail Gorbachev (1985-1991)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 4/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 3/10 (10/10 if we only count Americans) |

| Charisma,Innovation and novelty | 6/10 |

| Human Rights | 8/10 |

| Total: | 21/40 |

Mr. Naive gets a big bump thanks to an excellent human rights mark. Hesitant to follow his predecessors violations, he developed an image of the ultimate pushover. By all accounts, he was probably the most humane of the bunch. His main unforgivable problem was that he trusted his fellow homo sapiens too much. Especially his sordid and sneaky US counterparts. Whether the USSR was irreversably doomed or not is still an interesting point of conversation, but the fact remains that the dream dissolved during Gorbachev’s time.

Highlights

For good or bad, Gorbachev was the first Soviet leader to think of himself (and legitimately be considered) as a member of the intelligentsia. He was a lawyer rather than an engineer, at first deemed a breath of fresh air for hopeful reformists and democratization advocates. He gradually, if not rapidly, gave more power to the people and emasculated many of his heads and party elite. Although this would come back to bite him, it was a commendable act upholding the main virtues of both genuine socialism as well as democracy. He hesitated to ever use police and military power against revolutions, despite referendums at the time demonstrating he had the general public’s backing. He dreamt big of uniting the world, ending ‘nuclearism’, and retaining only the best principles of the socialist dream, while doing away with its cesspits.

Misha furthermore did his very best to prevent Bush’s Iraqi adventures. He had already convinced Saddam to withdraw from Kuwait, but the US traditional obsession with spreading democracy through invasions was stronger. His infamous Glasnost and Perestroika reforms (transparency and restructuring respectively) opened up Soviet society even more, permitting freedom of speech and press to the max.

Lowlights

It may have seem predestined, and mostly the result of policies, pressures and misses throughout the years rather than a result of Gorbachev’s actions, but Soviet Union’s dissolution was a shock. At least to those who grew up and gave their life towards the cause, it would seem the end wasn’t the result of a proper revolution or insane struggle. The natural progression, according to faithful Marxist followers, was supposed to be the end of capitalism rather than the end of socialism.

Misha simply conceded too much, to Germany especially, and all he ever really received in return was verbal agreements. US’ promises about the NATO’s expansion (or the lack thereof) were inexplicably believed. He just trusted the human nature too much, a curious characteristic for someone who was a great lawyer. The Eastern bloc found in his face a dear innocent grandpa, and effortlessly prepared their independence campaigns unbothered. Perhaps the greatest sign to what was about to follow was his being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for ending the Cold War, which, as we wrote recently, should never be deemed a good sign.

Deteriorating prices in oil never gave him a chance to bring his perestroika to fruition. The economy’s stagnation, partly caused by previous leaders, worsened and led to inflation and shortages. The previously thriving middle classes were worse off, and the fact that they had all the freedom to complain and lobby about it brought upon further waves of social rage.

Slightly overlooked fun fact

The West loved him so much that you wouldn’t exactly be a conspiracist if you thought he was just a kind-hearted, charismatic stooge who was there precisely to end the USSR. It certainly didn’t help matters when, back in 2007-long gone from the scene- he inexplicably agreed to star in a Louis Vitton/Berlin Wall double-edged sword advertisement. His earlier Pizza Hut cameo may have passed as a nice little quirky joke, but buddy, LV was his PR gone haywire, even if it supposedly wanted to promote other ideas. As someone who spent the vast majority of his career devoted to certain ideals (whether these were worthwhile or not is up to you), deciding to drop a deuce on his past for a lil’ extra cash is near inexcusable.

3. Leonid Brezhnev (1964-1982)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 5/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 7/10 |

| Charisma,Innovation and novelty | 4/10 |

| Human Rights | 7/10 |

| Total: | 23/40 |

Can barely believe Leo made it to the podium. Renowned for his eyebrows, hilarious medals obsession, and of course the immortalized socialist fraternal kiss with Honecker (still everybody’s favourite selfie when visiting the Berlin Wall), Brezhnev somehow managed to remain secretary for 18 years, despite being really ill throughout half of those. His reign has left its mark as the ‘Period of Stability’. That may sound lame, but in a planet ruled by apes gone berserk, it’s one more medal to Brezhnev’s unprecedented collection.

Highlights

The ordinary Soviet citizen lived a decent life during Brezhnev. This may have had more to do with high oil prices than with a genius strategy, but either way his first few years were marked by economic success. Education continued to flourish, and some availability to material goods allowed people to swallow the minimal capitalistic satisfaction pill with fewer regrets. Pensions increased, as did welfare benefits.

Importantly, the Soviets earned a lot of good rep through supporting anti-colonial movements in South American, African and Asian puppet states. They strove not to repeat the Cuban Missile Crisis, and stood up to the US regarding Vietnam, significantly helping the Viet Cong cause. As much as excessive military spending can be considered stupid and the effects of this spending would rear their ugly head later on, the state’s emphasis on defense during these years dissuaded much activity Cold-War wise, on top of helping rebels around the world wave the middle finger to European and American influence. As a result, it was at this time that the Soviet Union was first legitimately recognized as a superpower.

Lowlights

The already mentioned Soviet Afghan War, with its multiple repercussions, happened under Brezhnev’s watch. So did the 6-day war, a humiliation and letdown for Arabs, as Russia failed to provide meaningful support despite its seeming capabilities, allowing an Israeli crime which has shaped the region to this day. As said before, the invasion of Czechoslovakia was masterminded by Andropov, nonetheless, Brezhnev was the actual secretary of state at the time, meaning he rightfully got a lot of the blame. Relations with China soured, to the extent that the latter distrusted the USSR more than their archnemesis US. Of course, given China’s record at the time and the cultural revolution, perhaps this was another medal for Brezhnev’s heavy attire.

The augmented education levels and increasing accessibility to material goods led to a relative restlessness within the country. Having tasted the sweet lips of greed, people with white collar jobs (making around 500 rubles), began to resent how blue-collar workers’ wages were not that far off behind them. The latter earned a reputation for low productivity and inefficiency, furthering a sense of a sudden social divide. Readers of the time sensed an aura of social disappointment, where the fake bourgeoisie could ‘see’ but not ‘touch’ the wealths they craved. It didn’t help the cause that while most Soviet citizens had to wait in queues for a Lada, Brezhnev drove luxury vehicles (he was reportedly an awful driver) and made sure his own family gained access to things standard folk wouldn’t.

Slightly overlooked fun fact

In continuing with his medal and self-proclaimed courage mania, Brezhnev wrote a bunch of memoir-series books where his World War II adventures and accomplishments came to the surface. His books actually won the Lenin prize of literature, something which quickly became a running joke within the general public, provided not a single soul could be found who believed Leo actually authored them. It did not help his cause that his health barely allowed him to be present in high-profile events at the time, much less gift him the mental prowess to produce literature while undertaking General Secretary duties.

2. Nikita Khruschev (1953-1964)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 6/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 7/10 |

| Charisma,Innovation and novelty | 7/10 |

| Human Rights | 5/10 |

| Total: | 25/40 |

If you, along with me, were surprised Leo grabbed 3rd place, then Nikita’s silver might just be the straw that broke the camel’s back; where the reader finally chooses to give up. The King of De-Stalinization was a hell of a character. After decades of intense fear in criticizing anything Genocide-Joe (YES, the OG Genocide Joe was not Biden!), Khruschev went off with a bang.

Highlights

Hilariously, he set things straight about his emotions towards Stalin in an event which was termed ‘The Secret Speech’, though they didn’t manage to keep it secret from the local baker 14000km away. The story goes that the US leaked it, but we’ll be a little cautious with that conspiracy. To say Khruschev denounced Stalin in that talk would be an understatement. He crapped on the Purges and exposed little known details about them; he called Joseph a cult figure, with some of the accusations being so rough, that people reportedly got heart attacks or killed themselves upon hearing the diss delivered. The harsh talk was meant to be the start of a new policy for the USSR: one accentuating peaceful co-existence with the West. A reconciliation that should benefit all sides.

He followed up his talk with the renowned Thaw, namely a chilling out with the censorship and redaction of yester years. Banned novels and the like became accessible, contributing to newfound culture in the general masses. Nikita solidified nice tidbits such as the non-working weekend, as well as pioneered urban housing through large-scale projects. For the first time in the USSR’s history, families got to have their own flat and space as most households were till then shared by multiple families. The majority of people finished school, and all records were broken in terms of university attendance. Devoting resources to the above meant cutting down on army spending, a blunt and commendable decision during a volatile time spanning the Cold-War.

Last but not least, he humiliated the US in the space race. Sputnik became the first artificial satellite in space in 1957, while Gagarin the first human in looney-land four years later.

Lowlights

Nikita did make a name for himself as an impulsive nuthead. He’d insult people in public events (had a funny beef with everything concerning ‘pretentious’ art) after drunken barrages, as well as occasionally get stuck with silly ideas that weren’t going to work. Remained stubborn for the sake of it. His policies relative to agriculture, a self-proclaimed superproject, essentially tanked; he got obsessed with corn, for instance, just because the US loved it too, then failed miserably as the Soviet climate couldn’t handle it. Among with other silly efforts towards monoculture, and despite initial success in the program, food shortages eventually prevailed increasing disenchantment with his figure. Moreover, attempts at minor decentralization didn’t have the desired outcome for lack of proper planning, producing administrative chaos and needless dubiety.

Remember the Hungarian butchery? Well, Khruschev was head secretary when that happened. Same goes with the 1953 events during East Germany’s uprising. There was a ruthlessness and lack of hesitation in suppresing such revolutions, leading many to believe that Khruschev was not exactly a saint viewed through the Stalin prism. His most notable failure, nonetheless, involved the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Possibly the peak the Cold War ever really reached, Khruschev threatening nuclear war but eventually capitulating to US demands was a bit of a letdown for Soviet pride. Of course, there is an eye of the beholder aspect to the whole ordeal. Firstly, his actions did prevent a full-scale US invasion of Cuba. The public side of the agreement involved Soviets destroying their own nuclear weapons in the island, however, the silent side of the agreement also included the US dismantling their own nuclear capabilities in Italy and Turkey. It may seem reductive to put it this way, but at that moment Khruschev did seemingly sacrifice his image for the greater good.

Slightly overlooked fun fact

Likely Nikita’s most famous international moment came when he indignantly banged his shoe on the desk during a UN session, following certain accusations against his country. Though that’s a very cool theatrical moment, it never happened. In what must have been one of the first successful attempts of deepfakes and unnecessary disinformation, the whole thing seems to have been completely made up. Let’s be honest here, it was a win-win. The Soviets could claim that their boss is badass hot shit who won’t just sit there and take insults from the capitalists; the Westerners could keep brainwashing their cattle via the claim that he’s a hothead whose instability ignites and preserves Cold-War threats.

We’ll cheat and add another nugget to justify Niki’s position here. As aforementioned, he spent much of his career berating and ridiculing modern artists, waging war on work that wasn’t obviously and objectively awesome. Yet somehow, someway, he developed genuine relationships with many such artists upon retiring, the latter of whom reciprocated his appreciation. I’m willing to bet big that they smoked the best imported ganja during those sessions.

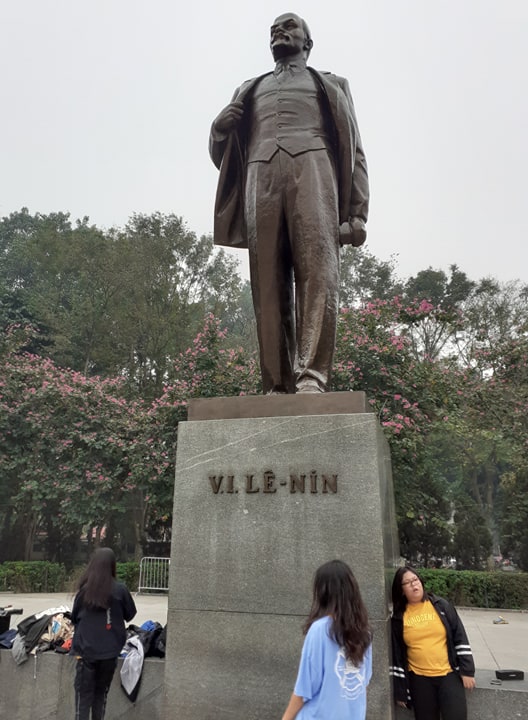

1. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ‘Lenin’ (1917-1924)

| Factor: | Score |

| Social advance and prosperity | 6/10 |

| Legacy and impact | 9/10 |

| Charisma,Innovation and novelty | 8/10 |

| Human Rights | 8/10 |

| Total: | 31/40 |

“The educated people are not the country’s brains, but its shits”. How can you say such a thing and not win gold? Much as we love underdogs and upsets, there was simply no grounds for any of the above individuals to dethrone the original G. Despite being the only Soviet leader who didn’t benefit from upward mobility (aka did not have humble beginnings)- his father possessed a respectable intellectual position as a renowned teacher- he was by all means a visionary and a real warrior. He truly cared about a fairer and more equitable society, and despite recognizing he wouldn’t live to see the half of it, he was happy to lay the groundwork even if it would scar his legacy.

The truth of the matter is a Revolution was coming. Working conditions and poverty, anti-war campaigns, worker’s rights, antivodka-prohibition revolts, nationalist tendencies throughout Russia’s other empires, protests were the rage. Lenin had the gift to package it all into one and become the face who would unite all these extremely diverging fronts into one Cerberus.

Highlights

Won’t turn this post into the manifesto, as it’s already too long as it is. While there is always an inherent difficulty in measuring impact precisely, he set the foundations for everything that was to come. Good and bad. We could write a book on Lenin’s policy, preternatural gifts, charisma, or love of cats but for now we’ll just focus on the lead-up to the revolution.

There was a time when, within the socialist competing factions, it seemed the Mensheviks would come on top as they were an undisputed majority. Lenin’s genius propaganda about Bolsheviks being the majority stems in the name itself. Back in 1898, he devised the name, coming from bolshinstvo (Russian for majority), after winning an arbitrary weekend-meeting style vote on central issues. That particular vote did not mean the Bolsheviks outnumbered the Mensheviks, as they were in fact significantly fewer for the entirety of the pre-Revolution era. Lenin did love wordplay, frequently using the name Bolshevik in speeches and meetings to imply a populist preference toward the faction. We are not here to argue that a simple name trick was the reason he prevailed over the Mensheviks, but it’s just an example of the man’s genius ploys and staying in touch with the masses’ pulse.

Lenin didn’t quite expect the revolution to come so sudden and effortless. Plainly put, his writings indicate that: i) he thought the revolution would start in Europe and not Russia, ii) he did not believe Russia had reached the natural stage where the Revolution would come as a natural heir, iii) The proletarians should go through an organic stage of ideological birth and advancement before they were ready to rebel. Strangely, that might sound more Menshevik than Bolshevik. All that said, he did wish for a Russian loss in World War I (war being an imperialist capitalist scourge). At a last moment revelation, he sensed that what initially seemed like ages away had miraculously showed up on his doorstep. It was this anti-war sentiment that once and for all would separate him from the Mensheviks (who also were against it in the majority, but loud voices within them not so much), and ultimately a leading reason why he received the backing he did later on.

Lowlights

Difficult to say if part of the violence employed during the Civil War was unnecessary. The White Army had a lot of despicable aspects to itself, so we’ll refrain from an opinion on the potential carnage, even though we do think it was much lesser than it would have been under other leaders. Lenin inherited a bit of a shithole. Post-war economy in shambles, the tsars having milked the place to the ground, starting anything of meaning required some sort of harsh decisions. But yes, even if we choose not to ignore context, authoritative tendencies and the implementation strategies towards the proletarian dictatorship could be argued against him.

Again, perhaps Lenin’s biggest failure was silently authorizing and at the same time underestimating Stalin. He did write how he was scared about Joe’s growing power in his Last Testament, but that was too little too late, and the document remained hidden by Stalin for many years. All said and done, the first leader and pioneer of the Revolution should have thought better about who would continue and represent his legacy. His failing health certainly didn’t help matters, but you would like to think someone with his savvy would do better work preparing the ground.

Slightly overlooked fun fact

Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, was a key face in the Revolution herself. Passionate about improving education of the masses (perhaps the most important aspect uniting her to Lenin), she played a huge role enhancing the status of women as well as fostering librarianship. A lesser known spicy gossip is the role of Inessa Armand, another important revolutionary feminist, entrenched in Lenin and Krupskaya’s love life. Historical accounts tell us that both Lenin as well as Nadezhda may have been infatuated with her. Was this a case of hidden polyamory? And if so, why didn’t Lenin promote this sexual plurality, forcing civilization to instead wait a bunch of decades since it became accepted practice? Was it a more plain love triangle, where husband and wife didn’t really have the hots for each other, but they were both in love with the same woman and agreed to share her? We’ll never know.